2017 cyberattacks on Ukraine = Petya malware

2017 cyberattacks on Ukraine

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

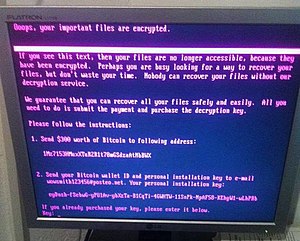

Petya's ransom note displayed on a compromised system

| |

| Date | June 27–28, 2017 |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Type | cyberattack |

| Cause | malware, ransomware, cyberterrorism |

| Outcome | affected several Ukrainian ministries, banks, metro systems and state-owned enterprises |

| Suspect(s) | |

Contents

[hide]Approach[edit]

Security experts believe the attack originated from an update of a Ukrainian tax accounting package called MeDoc (M.E.Doc).[2] MeDoc is widely used among tax accountants in Ukraine,[13] and the software is the main option for accounting for other Ukrainian businesses, according to Mikko Hyppönen, a security expert at F-Secure.[2] MeDoc provides periodic updates to its program through an update server. On the day of the attack, 27 June 2017, an update for MeDoc was pushed out by the update server, following which the ransomware attack began to appear. British malware expert Marcus Hutchins claimed "It looks like the software's automatic update system was compromised and used to download and run malware rather than updates for the software."[2] The company that produces MeDoc claimed they had no intentional involvement in the ransomware attack, as their computer offices were also affected, and they are cooperating with law enforcement to track down the origin.[14][13] Similar attack via MeDoc software was carried out on 18 May 2017 with a ransomware XData. Hundreds of accounting departments were affected in Ukraine.[15]It was shown that the domain used for updating MeDoc software was served by a single host located at WNet Internet-provider server.[16] Previously, on June 1, Ukrainian security agency SBU raided offices of WNet, claiming that it passed its technical facilities to a firm controlled by Russian intelligence agency FSB.[17] Since the domain was configured to a very short TTL of 60 seconds, the provider could easily redirect all update traffic to a fake host with malware disguised as MeDoc updater within a short period of time.[16]

The cyberattack was based on a modified version of the Petya ransomware. Like the WannaCry ransomware attack in May 2017, Petya uses the EternalBlue exploit previously discovered in older versions of the Microsoft Windows operating system. When Petya is executed, it encrypts the Master File Table of the hard drive and forces the computer to restart. It then displays a message to the user, telling them their files are now encrypted and to send US$300 in bitcoin to one of three wallets to receive instructions to decrypt their computer. At the same time, the software exploits the Server Message Block protocol in Windows to infect local computers on the same network, and any remote computers it can find.

The EternalBlue exploit had been previously identified, and Microsoft issued patches in March 2017 to shut down the exploit for the latest versions of Windows Vista, Windows 7, Windows 8.1, Windows 10, Windows Server 2008, Windows Server 2012, and Windows Server 2016. However, the WannaCry attack progressed through many computer systems that still used older Windows operating systems or previous releases of the newer ones, which still had the exploit, or that users had not taken the steps to download the patches. Microsoft issued new patches for Windows XP and Windows Server 2003 as well as previous versions of the other operating systems the day after the WannaCry attack.

Security experts found that the version of Petya used in the Ukraine cyberattacks had been modified; it encrypted all of the files on the infected computers, not just the Master File Table, and in some cases the computer's files were completely wiped or rewritten in a manner that could not be undone through decryption.[18][19] There also has yet to be discovery of a "kill switch" as there was with the WannaCry software, which would immediately stop its spread.[20]

Attack[edit]

During the attack the radiation monitoring system at Ukraine's Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant went offline.[21] Several Ukrainian ministries, banks, metro systems and state-owned enterprises (Boryspil International Airport, Ukrtelecom, Ukrposhta, State Savings Bank of Ukraine, Ukrainian Railways) were affected.[22] In the infected computers, important computer files were overwritten and thus permanently damaged, despite the malware's displayed message to the user indicating that all files could be recovered "safely and easily" by meeting the attackers' demands and making the requested payment in Bitcoin currency.[23]The attack has been seen to be more likely aimed at crippling the Ukrainian state rather than for monetary reasons.[13] The attack came on the eve of the Ukrainian public holiday Constitution Day (celebrating the anniversary of the approval by the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament) of the Constitution of Ukraine on 28 June 1996[24]).[25][26] Most government offices would be empty, allowing the cyberattack to spread without interference.[13] In addition, some security experts saw the ransomware engage in wiping the affected hard drives rather than encrypting them, which would be a further disaster for companies affected by this.[13]

A short time before the cyberattack began, it was reported that an intelligence officer and head of a special forces unit, Maksym Shapoval, was assassinated in Kiev by a car bomb.[27] Former government adviser in Georgia and Moldova Molly K. McKew believed this assassination was related to the cyberattack.[28]

On 28 June 2017 the Ukrainian Government stated that the attack was halted, "The situation is under complete control of the cyber security specialists, they are now working to restore the lost data."[11]

Attribution[edit]

On 30 June, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) reported it had seized the equipment that had been used to launch the cyberattack, claiming it to have belonged to Russian agents responsible for launching the attack.[29] On 1 July 2017 the SBU claimed that available data showed that the same perpetrators who in Ukraine in December 2016 attacked the financial system, transport and energy facilities of Ukraine (using TeleBots and BlackEnergy[30]) were the same hacking groups who attacked Ukraine on 27 June 2017. "This testifies to the involvement of the special services of Russian Federation in this attack," it concluded.[7][31] (A December 2016 cyber attack on a Ukrainian state energy computer caused a power cut in the northern part of the capital, Kiev.[7]) Russian-Ukrainian relations are at a frozen state since Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea followed by a Russian government-backed separatist insurgency in eastern Ukraine that by late June 2017 had killed more than 10,000 people.[7] (Russia has repeatedly denied sending troops or military equipment to eastern Ukraine.[7]) Ukraine claims that hacking Ukrainian state institutions is part of what they describe as a "hybrid war" by Russia on Ukraine.[7]On 30 June 2017, cyber security firm ESET claimed that the Telebots group (which they claimed had links to BlackEnergy) was behind the attack: "Prior to the outbreak, the Telebots group targeted mainly the financial sector. The latest outbreak was directed against businesses in Ukraine, but they apparently underestimated the malware's spreading capabilities. That's why the malware went out of control."[7] ESET had earlier reported that BlackEnergy had been targeting Ukrainian cyber infrastructure since 2014.[32] In December 2016, ESET had concluded that TeleBots had evolved from the BlackEnergy hackers and that TeleBots had been using cyberattacks to sabotage the Ukrainian financial sector during the second half of 2016.[33]

Affected companies[edit]

Companies affected include Antonov, Kyivstar, Vodafone Ukraine, lifecell, TV channel STB, TV channel ICTV, TV channel ATR, Kiev Metro, UkrGasVydobuvannya (UGV), gas stations WOG, DTEK, EpiCentre K, Kyiv International Airport (Zhuliany), Prominvestbank, Ukrsotsbank, KredoBank, Oshchadbank and others,[11] with over 1,500 legal entities and individuals having contacted the National Police of Ukraine to indicate that they had been victimized by the 27 June 2017 cyberattack.[34] Oshchadbank was again fully functional on 3 July 2017.[35]While more than 80% of affected companies were from Ukraine, the ransomware also spread to several companies in other geolocations, due to those businesses having offices in Ukraine and networking around the globe. Non-Ukrainian companies reporting incidents related to the attack include A.P. Moller-Maersk, FedEx and the COFCO Group.[36] A police officer believes that the ransomware attack was designed to go global so as to detract from the directed cyberattack on Ukraine.[37]

Reaction[edit]

Secretary of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine Oleksandr Turchynov claimed there were signs of Russian involvement in the June 27 cyberattack, although he did not give any direct evidence.[38] Russian officials have denied any involvement, calling Ukraine's claims "unfounded blanket accusations".[29]NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg vowed on 28 June 2017 that NATO would continue its support for Ukraine to strengthen its cyber defence.[39]

Comments

Post a Comment